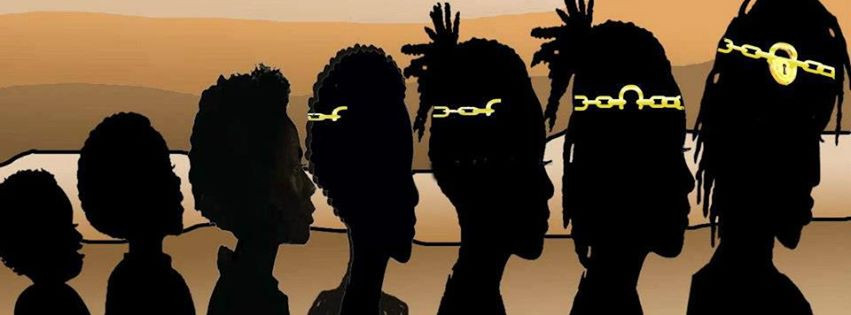

In “Decolonising the Higher Education Curriculum: An Analysis of African Intellectual Readiness to Break the Chains of a Colonial Caged Mentality” (Nyoni, 2019), Jabulani Nyoni exposes how the “caged colonial mentality” continues to shape African education long after the end of colonial rule. Although Nyoni’s critique focuses on higher education, its implications reach much further—into the very foundations of schooling. If the colonial cage is to be broken, the process must begin in the K–12 classroom, where young minds first learn what knowledge is worth knowing and whose voices deserve to be heard.

Nyoni’s argument that “failure to unchain or de-cage the ‘caged’ mind will mean that decolonial efforts will do nothing more than offer patently cosmetic changes that remain marooned within Western knowledges and practices” (p. 7) speaks powerfully to early education. Across much of the K–12 curriculum in Africa and the diaspora, Western narratives still dominate history, literature, science, and even moral education. African stories, indigenous knowledge systems, and communal philosophies are often added as cultural supplements rather than integrated as intellectual equals. This imbalance reinforces the very mentality Nyoni warns against—a belief that excellence, logic, and truth come only from Western sources.

To decolonize K–12 education, curriculum developers and teachers must consciously reorient schooling toward an Afro-communalitarian model that honours interdependence, community, and spiritual wholeness. Lessons should foreground African authors, scientists, inventors, and thinkers—not as occasional figures in diversity units, but as core architects of global knowledge. As Nyoni (2019) insists, “African intellectuals should not continue referencing Foucault, Rousseau, Hegel… but invariably counterbalance their views with authors who come from Africa to advance African epistemologies” (p. 3). In K–12 settings, this means giving equal weight to figures like Cheikh Anta Diop, Wangari Maathai, or Wole Soyinka when teaching history, science, and literature.

Early education is where mental liberation must take root. When children learn to see Africa as a center of wisdom and creativity, they grow into adults capable of leading decolonial transformation rather than reproducing colonial hierarchies. The task, therefore, is not merely to adjust curriculum content, but to transform the purpose of education—from conformity to awakening. As Nyoni (2019) concludes, true decolonisation demands “the dismantling of systemic [colonial mentality] and the embrace of seismic shifts that build on appropriate knowledge, competences, skills, values, beliefs and practices from around the globe, while retaining Africa’s interests at the centre” (p. 1).

The decolonial project must begin early—before the cage hardens.

Reference

Nyoni, J. (2019). Decolonising the higher education curriculum: An analysis of African intellectual readiness to break the chains of a colonial caged mentality. Transformation in Higher Education, 4(0), a69. https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v4i0.69